By studying individuals in “dual debt” to both the child support and criminal legal systems, the authors find that alienating and conflicting policy processes can trigger cycles of legal anomie and system avoidance, especially amongst economically and socially vulnerable individuals.

AMHERST, Mass. – Legal cynicism and legal estrangement are well-established concepts amongst sociolegal scholars. But how do negative perceptions of the law and strategic disengagement inform one another?

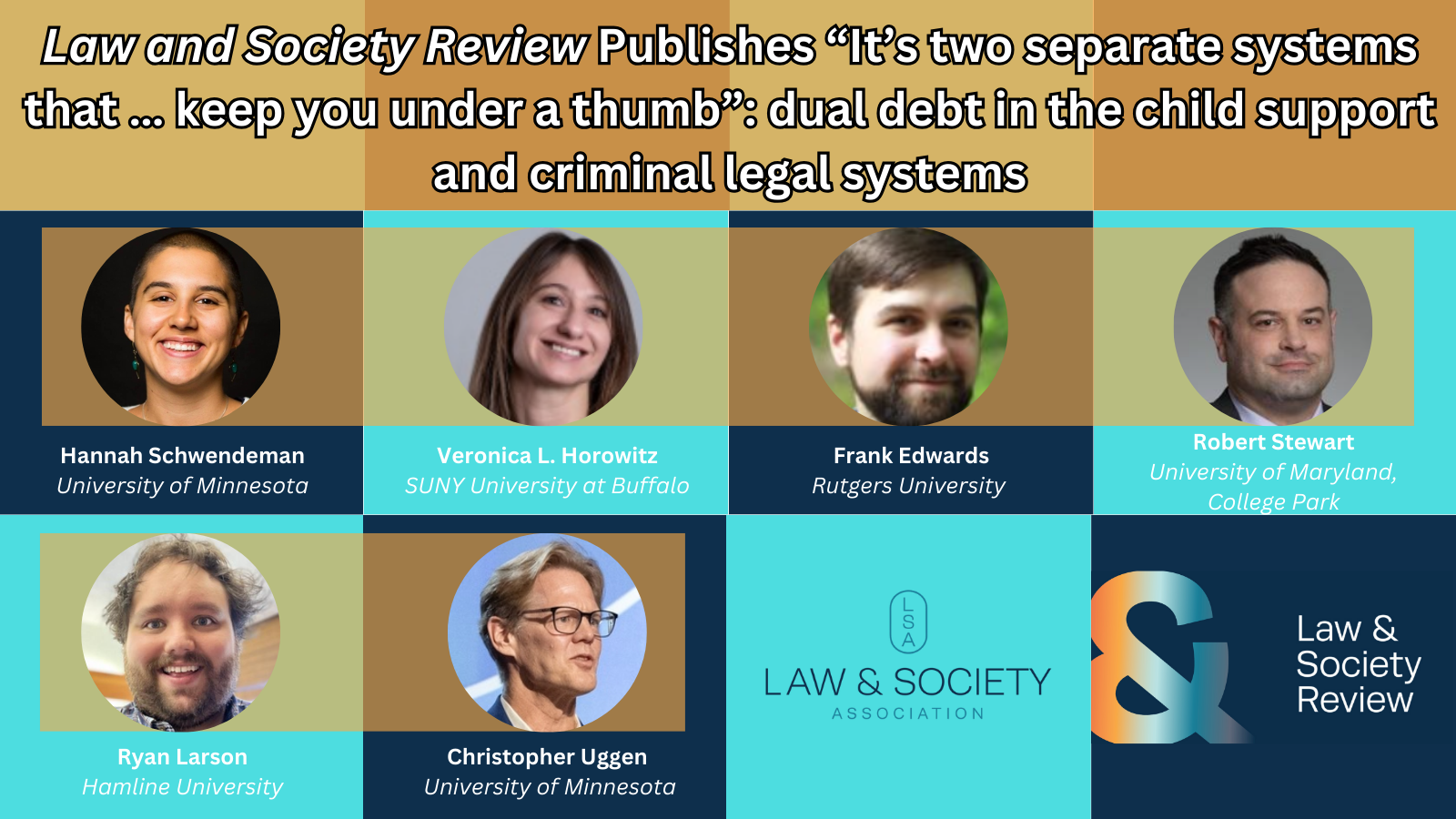

Scholars Hannah Schwendeman (University of Minnesota), Veronica L. Horowitz (SUNY-University at Buffalo), Frank Edwards (Rutgers University), Robert Stewart (University of Maryland, College Park), Ryan Larson (Hamline University), and Christopher Uggen (University of Minnesota) address this question in their December 2024 Law and Society Review article.

From September 2018 to March 2020, the authors interviewed 30 Minnesota residents indebted to both the criminal legal and child support systems—a circumstance the authors describe as “dual debt,” wherein individuals find themselves simultaneously engaged in welfare and punishment systems whose policies and mandates often contradict one another. By orienting their research around questions such as

“How do people navigate the experience of dual debt?”

“How do they conceive of these systems and their relationship to them?” and

“How do these simultaneous debts impact their lives and plans for the future?”

Schwendeman and her colleagues develop and propose a conceptual model that illustrates how “alienating policy processes” can increase legal cynicism, thereby increasing system avoidance, resulting in additional debt and criminal penalties, whereupon the cycle begins again.

As the authors point out, the most common punishments doled out by the U.S. criminal system are financial in nature—from fines and restitution to fees and surcharges. Most people would rather be presented with a hefty bill than a pair of handcuffs, but if they are unable to pay, the consequences can quickly snowball. These individuals are more likely to struggle with caring for their basic needs and expenses, leading to the degradation of their mental health, physical health, and interpersonal relationships. Financially, they face declining credit scores, wage garnishment, intercepted tax returns, lawsuits, and potentially even the very imprisonment they were initially relieved to avoid.

When it comes to child support, nonpayment is broadly viewed as the behavior of so-called “deadbeat” dads, but the authors cite research showing that most parents who accrue child support debt do so because they are unable, rather than unwilling, to pay. Depending on the state, consequences for this can include suspended driver’s licenses, asset seizure, intercepted tax returns, and incarceration.

Individuals with both criminal legal debt and child support debt tend to owe significantly higher amounts in both systems than those indebted to just one. Criminal records make it harder to obtain employment on the formal job market, which in turn makes it more difficult to manage daily living expenses, much less hefty debt obligations. As the debt grows larger, so too do the obstacles to paying off that debt—lost licenses lead to even fewer employment opportunities, wage garnishment throws individuals even further into poverty, and individuals recently released from prison find themselves reentering the world with even more debt accrued during their sentence.

These harsh realities often result in “legal anomie,” a term the authors, citing Émile Durkheim, describe as “a state of normlessness that results from broken social bonds and social disorder via the law and legal authorities.” This phenomenon is characterized by a belief that the social world is chaotic, as well as feelings of alienation and despair.

“While individuals might agree with the principles of the criminal legal system or the child support system, their experience led them to see their actual processes as harmful,” the authors explain. “Consistently, interviewees saw the systems as counterproductive because the consequences for nonpayment hindered their ability to pay outstanding debts.”

This negative perception of legal systems is compounded by ongoing social stigma. As one interviewee shared: “I feel like my right arm should be ‘debt’ and my left arm should be ‘felony’, ‘cause that’s what everybody sees when they look at me. That’s all that I am. When I’m trying to get a car, or an apartment, or whatever. And when I call and try and pay any of my debt off, they talk to me like I’m a piece of crap.”

When policy processes fail to both achieve their purported aims and accommodate the humanity in all parties involved, “system avoidance,” defined as “the process of dissociating and disconnecting from social institutions that keep formal records in order to reduce surveillance,” becomes more viable—or in some cases, borderline necessary.

Describing his experience with wage garnishment, another interviewee shares: “I would’ve gotten maybe like $140 at each check to live off for two weeks. And I was homeless. I just quit my job. I just went back to the streets, there’s no way I’m going to let people just take my money, and I’m not going to work this job and only have $140 because it’s just going to make me hopeless, even more hopeless than I am. So that’s when I basically stopped working legitimate jobs.”

To avoid accruing additional debt or having their assets seized, individuals with overwhelming dual debts may go “off-grid” by only working informal jobs, participating in cash transactions, and/or cancelling bank accounts. Over time, this strategy leads to worsening inequalities due to decreased credit scores and a diminished ability to get loans, finance cars, or find housing. To manage their mental and emotional wellbeing, such individuals may also engage in “information avoidance,” avoiding mail, phone calls, and other correspondence that reminds them of harsh financial realities that they feel powerless to fix.

You can learn more about Volume 58, Issue 4 here. LSA members have access to this volume and the entire back catalog of LSR via Cambridge University Press here.